HTML & CSS structure at StreetHub

Namespacing, context, and portability

- #design

- @Jeremy

- ☼ 08 Nov 2014

Undertaking a complete overhaul of a front-end design is the opportunity to setup a readable, meaningful and hopefully maintainable structure for both HTML and CSS, as they are obviously closely related.

As anything you can iterate upon, it's hard to reach the point where you finally decide:

"Ok, that's the structure I'm going for."

There's always room for a better approach. You want to prevent your future-self from having to go through all the templates and stylesheets again. But you need to ship the new website in time.

So where do you start? With the content of course.

HTML Structure

Writing HTML is a constant compromise between conciseness and flexibility: enough structure to cover all elements, while avoiding injecting superfluous markup. After all, your CSS will end up populating your HTML with more hierarchy anyway.

You want your structure to be future-proof, which means being able to:

- add new pages easily, without having to think twice about what structure to adopt

- alter existing pages without disrupting the whole layout

- prevent potential conflicts between common elements (header, footer) of different pages

- insert re-usable elements throughout the website

- provide context for these re-usable elements

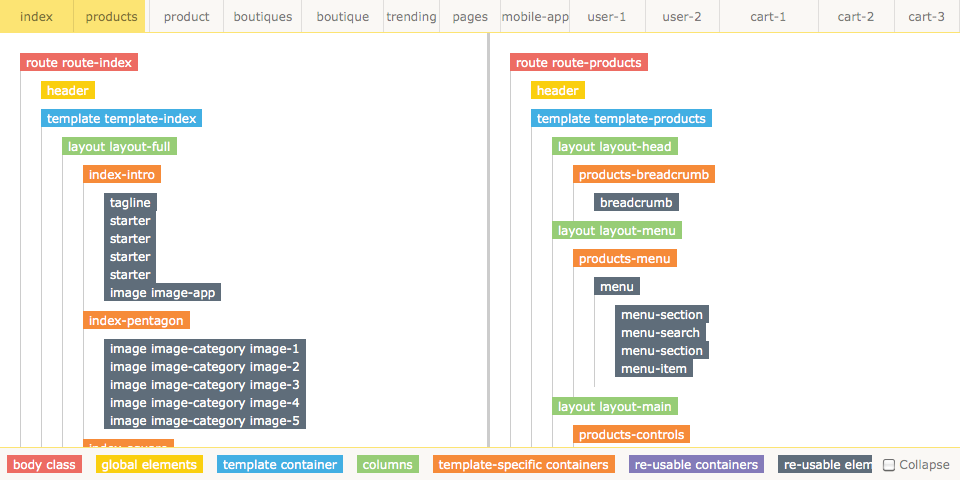

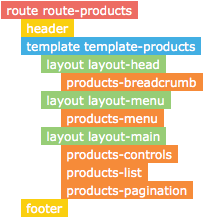

Overview:

|

body class |

Can alter the body itself, or any global element (header, footer) |

|---|---|---|

|

global elements | Present on each page of the website. |

|

page container | Encompasses the whole template. Sibling of global elements. |

|

visual structure | Main sections of a page, mainly columns. |

|

template-specific blocks | Level of hierarchy meant to contextualize the children of this template only. |

|

containers for elements | Blocks that are only meant to contain other elements, and wouldn't exist withtout them. |

|

reusable elements | Self-sufficient elements, that have a styling of their own, can be reused throughout the website, and be altered by the context. |

"Use the route, Luke!"

The 3rd level in the HTML hierarchy is where all template-specific blocks are. Their CSS classes are systematically prepended with the route's name.

Why? Namespacing.

It becomes harder overtime to come up with accurate names for your elements. It's especially true if you mostly elements that aren't meant to be reused. The homepage (/index) almost only comprises single-use blocks. If I were to find relevant names for each of them, I'd populate the namespace with selectors that might have made more sense for reusable elements.

The prefix provides the ability to reuse the second part of the CSS class: products-controls and boutiques-controls can exist simultaneously, without actually needing to look alike.

This automatic naming approach makes it very easy to name this level of blocks whenever another template is created. It's simply: the route + a dash + and anything that makes sense. Any naming conflict is avoided.

It also makes the CSS easier to read vertically.

Direct-child influence

CSS priority can become overwhelming. For one, I only use CSS classes, considering how ids are powerful and how generic selectors aren't.

I also limit the scope of descendant selectors by trying to stick to a simple rule:

Any element can only be altered by its direct parent.

route-productscan alter the header, but not anylayout- a

templatecan only alter alayout - template-specific containers like

products-menucan only alter themenuthat's inside

Because the route is appended to route- and to template-, there's no need to use .route-products .template because .template-products can be used.

And because the route is prepended to all template-specific selectors like products-menu, there's no need to make use of an ancestor like route-products or template-products.

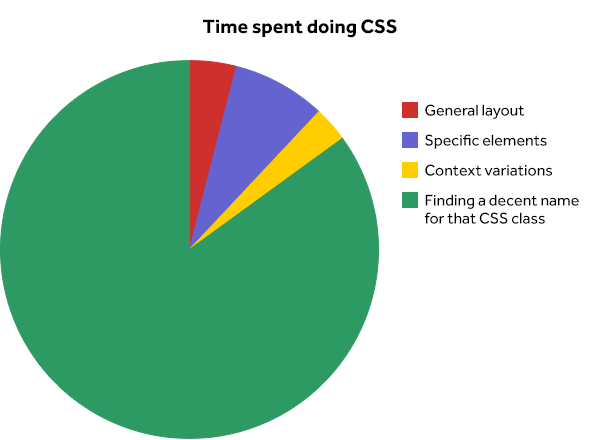

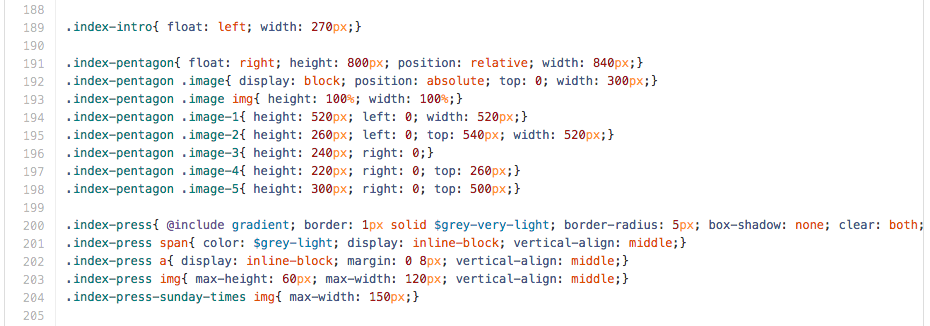

(S)CSS sanity

It's the first time I use a CSS pre-processor in production. I've always managed to keep my CSS short (I write in line for a higher density of information and better vertical readibility of selectors), but mostly meaningful, by combining selectors with shared properties, keeping descriptive names for selectors, avoiding repeating myself, and altering styles according to context.

Using a CSS framework hasn't even crossed my mind. A framework has its benefits though, especially for developers who don't want to touch any stylesheet, or for functional dashboards that solely comprise forms, columns, and buttons. But I would have spent more time overriding default styles, which would have restricted my ability to design distinct elements.

CSS structure

StreetHub.com is a large-enough project for me to separate my stylesheet into multiple files.

00-reset.scss |

HTML5 reset | *{ margin: 0; padding: 0;} doesn't seem to do the trick anymore. |

|---|---|---|

01-font.scss |

Icon font | Initially created for the iPhone app, it made sense to reuse it for the desktop app: as flexible as text (especially for color and size), and kind of Retina-ready. |

02-mixins.scss |

SCSS variables and mixins | Mandatory, considering the compatibility requirements and size of the project. |

03-global.scss |

Global elements | For elements that appear on every page: the header (including the nav), the verstaile container, and the footer. Styling of generic tags is also included. |

04-elements.scss |

Reusable elements | Both reusable and self-sufficient. They act like components that appear here and there, in different contexts, even several times within the same page. Titles, buttons, images, dropdowns, tags, icons... Classes are ordered alphabetically because it's the best future-proof strategy there is. |

05-modifiers.scss |

Context variations | When you alter an element within another element. Like an icon within a button. Or a button within a title. Or a dropdown within a title. Or an icon within a dropdown within a title... It's mostly icon variations. This stylesheet must come after 04-elements considering the styling applied are just adjustments of already defined properties. |

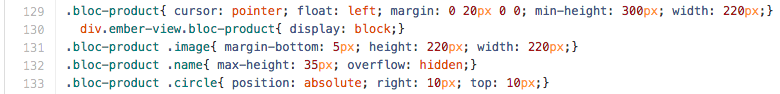

06-containers.scss |

Blocks containing other elements | They are not self-sufficient and only contain other elements, meaning they only exist because of their children. Example: bloc-product which contains image name price stamp and circle.The bloc-product acts a container for these components, but wouldn't exist without them.This stylesheet also includes template containers, layout elements, and lists. |

07-fancy.scss |

Cool stuff | For CSS transitions mostly, but also all the z-index values. Considering these values are relative, it's easier to group them altogether. |

08-animations.scss |

Even cooler stuff | Animations are fun to watch but are far from mandatory. They're kept in a separate stylesheet in case I want to disable them, and because keyframes take up a lot of space. |

09-responsiveness.scss |

Mobile-last approach | With 3 breakpoints:

|

Namespacing = readability + sanity

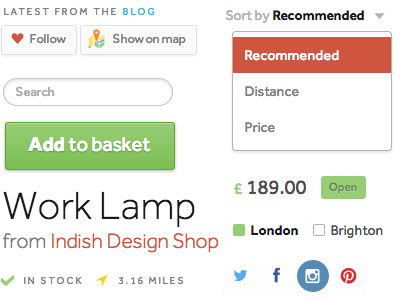

It's easy to find names for elements: considering how they can exist without any context, a descriptive name (not of the styling but of the meaning) is straightforward. .button for buttons, .tag for tags, .price for price...

It's also easy to run out of relevant names for everything else, especially containers. My strategy is to prefix containers (specific or reusable ones), making them 2-worded, and leave elements the dictionary's exclusivity.

Container vs. element

Buttons, images, checkboxes, icons, prices, titles, subtitles, content holders, dropdowns, tags... are elements.

They are:

- self-sufficient: they carry a styling of their own

- portable: usable anywhere on the website, anywhere within a page

- alterable: by the context in which they appear

- simply named: their CSS class is a single word (apart from element variations)

It's hard to draw the line between what can be an element and what acts as a mere block container for other elements. I just ask myself:

"Would this element exists on its own, without its children?"

If not, it's a block.

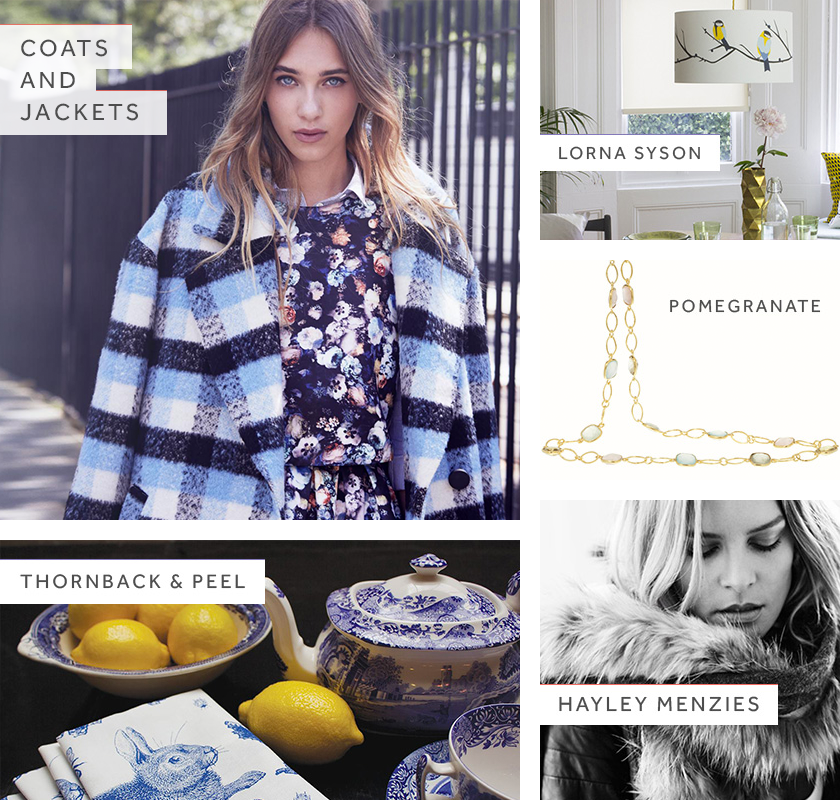

Template-specific vs. reusable blocks

Blocks can either be reused (like elements) or only appear in one template.

On the homepage, there is a mosaic of images. It's called index-pentagon, because it's on the homepage (/index route) and it has 5 images.

Is index-pentagon unique throughout the website? Yes. It can thus keep its route-prefixed CSS class because it won't be reused anywhere else.

It also makes the HTML element and the CSS selector both easily identifiable:

- if I'm messing with the HTML and need to make some CSS changes, I know exactly where to find it

- if I'm browsing my CSS, I can easily tell what each line targets in the HTML

The added fact of writing my CSS in line helps defining a clear visual hierarchy: I can scan the CSS and see the HTML structure.

What about bloc-product?

It appears on the homepage, the wishlist, the boutique page, the cart... Its CSS class can't include the route, considering its portability. It's named bloc-product instead of product to differentiate it from self-sufficient elements. The prefix helps this distinction while preserving the namespace (in case I actually need a product element).

Its CSS is very light: considering it's a container for elements, and because these elements already have a style of themselves, there's nothing much left to alter.

Selectors order

The order in which selectors appear has an impact on the style ultimately applied: for 2 equally-weighted selectors, the latter will have precendence. But considering:

- my strategy of only letting direct parents have an impact (in non-single selectors)

- my choice of using CSS classes exclusively

- the order in which files are called by the preprocessor

CSS priority is not a major concern.

It's only one in 05-containers.scss. First you'll find bloc- and layout- blocks, which are both reusable. The rest of the file is ordered by route, where reusable blocks can be altered within the context of a template-specific block.

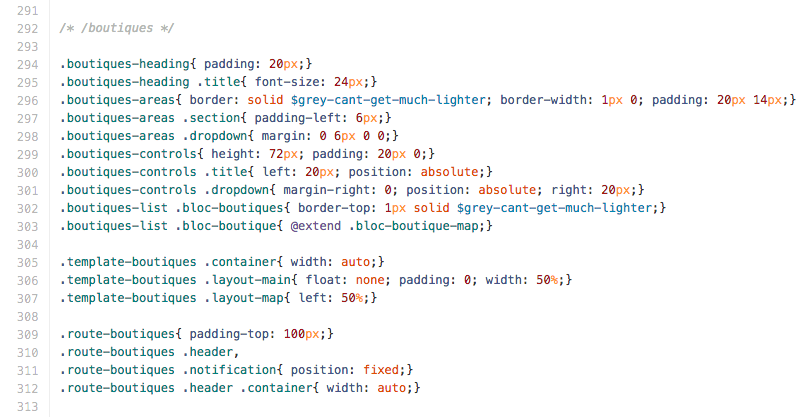

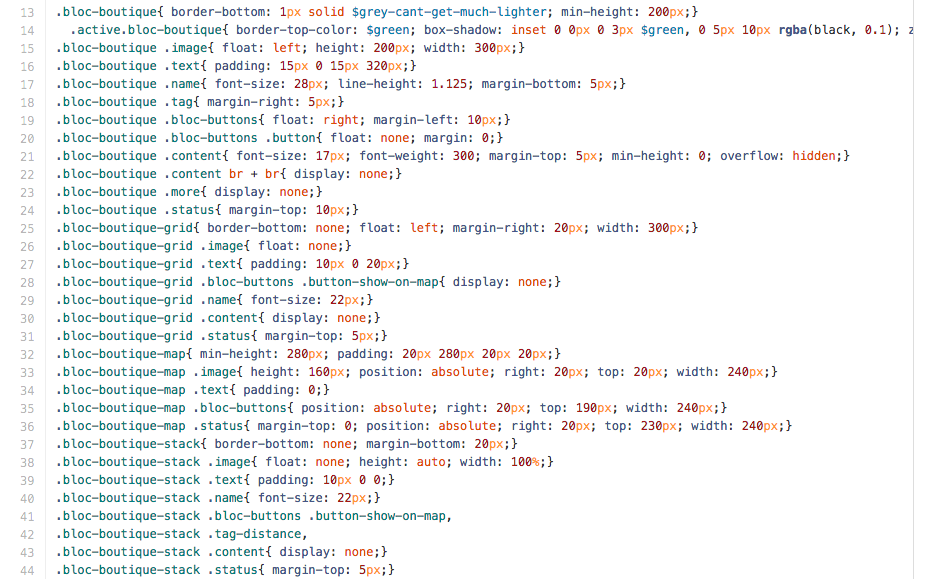

For example, the /boutiques route looks like this:

There are:

- template-specific blocks, like

.boutiques-heading - reusable blocks altered by template-specific ones, like

.boutiques-list .bloc-boutiques - template and route blocks, which alter already defined blocks and elements

Abstraction of style alternatives

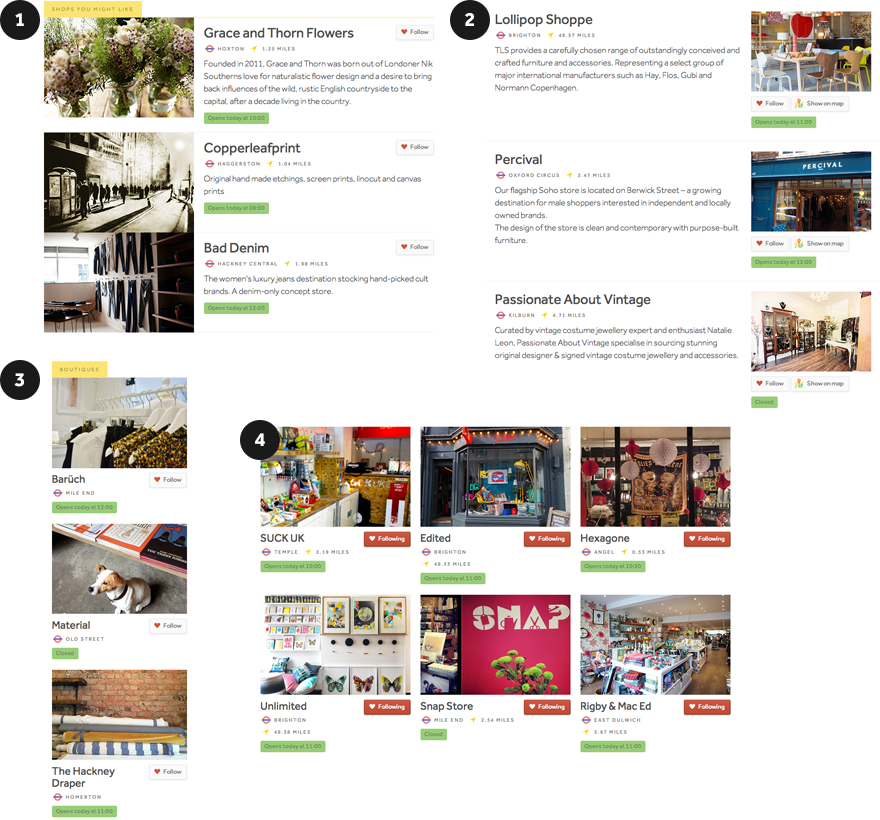

The .bloc-boutique has 4 different layouts that all use the exact same HTML markup.

How do you define 4 different styles?

- through a parent selector, and define specific styles within that context. We could have

.list-boutiques-grid .bloc-boutique.list-boutiques-flat .bloc-boutiqueand.list-boutiques-vertical .bloc-boutique - with an additional class, and have

.bloc-boutique.bloc-boutique-cell. It's semantically less inspired than the "grid list".

In any case, we want to alter the HTML code as less as possible, or even not at all. Considering that the markup is already populated with template-specific contextualizers, it's easy to use them to choose which layout we want for each template.

Thanks to SCSS, the abstraction can remain within the stylesheet, leaving the HTML structure consistent and identical throughout the templates, and, dare I say, semantic.

What is ultimately altered in each case? It's .bloc-boutique. So let's write the default style and its variations:

The naming is not exactly semantic: "grid" and "stack" describe the visual layout, whereas "map" tells where it should be used. If we were to use these class names in the HTML markup, I would break the golden rule I try to constantly follow:

HTML is for content, CSS is for layout

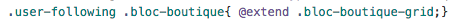

Thankfully, SCSS provides the @extend method, which allows applying all the styles of a class to another class. In my case, I use it to apply additional styles within a context:

On the user account page where all the boutiques he's following are listed, I want the boutiques to appear in a grid. In a single CSS property, I just call all the styles (children included) of .bloc-boutique-grid, without having to alter any HTML.

Choosing another of the predefined layouts would require changing a single word only.

Best approach (so far)

We launched StreetHub.com's latest version 3 months ago. The adopted HTML/CSS structure has proven to be:

- flexible enough for page additions

- readable enough for design alterations

- meaningful enough to perform quick fixes

Unlike programming languages, HTML and CSS don't exactly have best practices. You just refine through common sense your decisions over the years, and avoid cramming your code with unreadable patterns.

I'm not sure I'll ever reach a point where I'll be completely satisfied with my approach, where any theoretical flaw would be nonexistent and any reconsideration futile.

I wish I never will: it would be utterly boring.